301 Moved Permanently

Streamlining and certainty. These are the two words that you most often hear when you talk to developers about needed permitting and environmental reforms.

Lately, these words have also been batted around with increased frequency by California’s legislators and government decision-makers as they grapple with how to spur economic growth and meet the state’s mandate to generate a third of its electricity from renewable resources by the end of the decade.

This article will describe the most significant considerations for siting and permitting a utility-scale solar project in California today, along with some positive legal developments that could increase the speed and certainty of the permit process tomorrow.

Utility-scale solar projects require hundreds, sometimes thousands, of acres of land. Finding an ideal site in California almost always requires a balancing of environmental and development factors. Although any successful project needs to be located in an area with adequate solar insolation and ideally should be close to existing or planned transmission facilities, a developer also needs to consider the environmental characteristics of a site and the associated risk of costly and time-consuming permitting. It should come as no surprise that the greatest permitting risks in California involve biological and agricultural resources.

Nothing can slow down a project approval or scare away potential investors like the presence of special-status species. Even when a site is devoid of special-status species, the historic use of the site by such species can trigger increased scrutiny by government decision-makers and interested parties.

Thus, early efforts to screen out biologically significant sites can pay off in the long run. In particular, avoiding sites that contain endangered or threatened species or critical habitats protected under the federal or state endangered species acts can help avoid significant delays and uncertainty associated with consultation with the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service and/or the California Department of Fish and Wildlife.

In general, depending on the scope of a project’s impacts on protected species, it can take one to two years or more to obtain the agencies’ authorization to incidentally “take” protected species. Furthermore, the process can result in substantial project changes and the imposition of costly conditions.

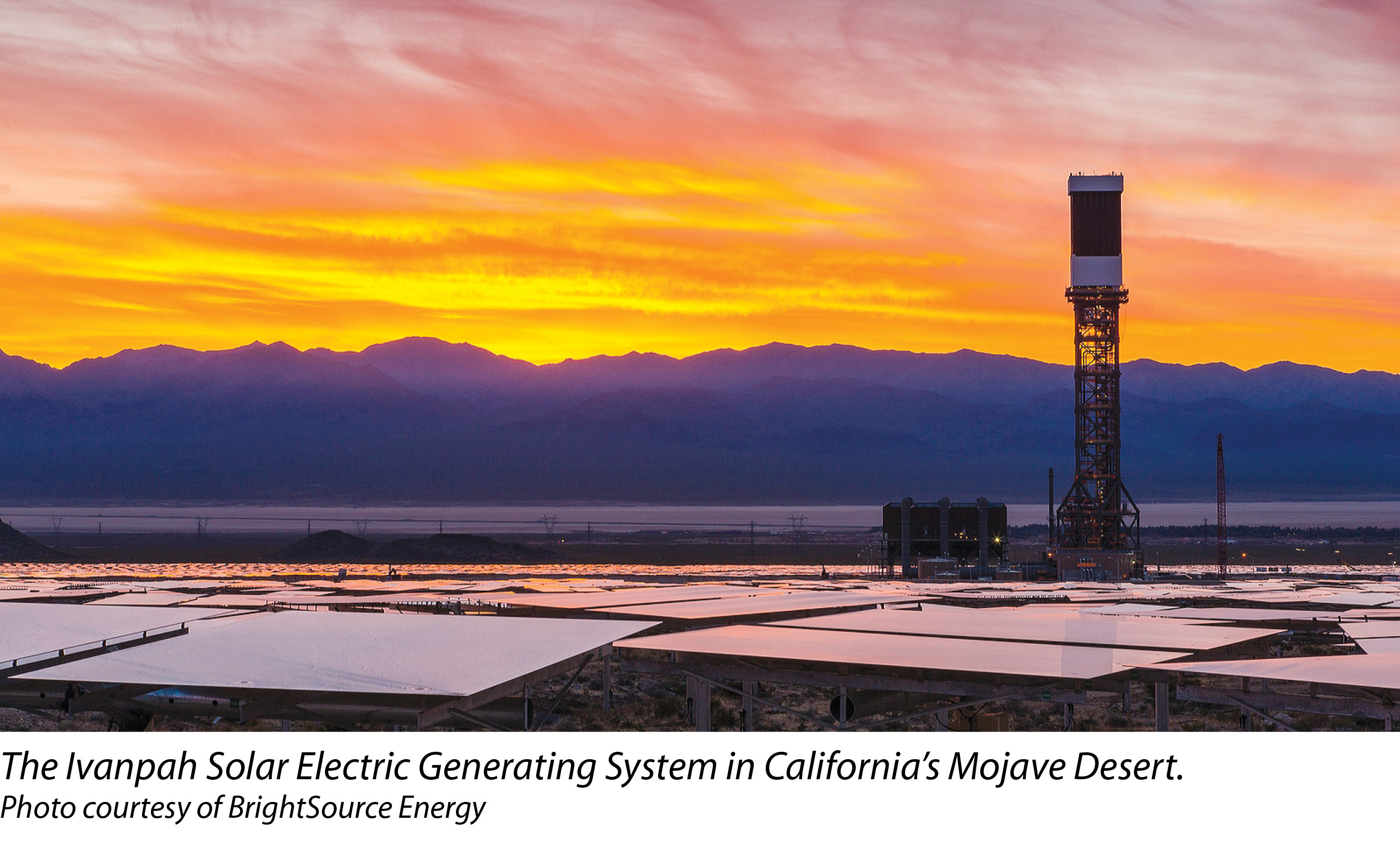

For example, it is widely reported that the sponsors of the 392 MW Ivanpah solar thermal project located in the California desert spent upward of $60 million in mitigating the project’s impacts on the desert tortoise, a species protected under federal and California law. It is also not uncommon for agencies to require compensatory mitigation land at a ratio of 1:1 to 3:1 or greater.

Although these considerations have, in some cases, caused project developers to avoid sensitive, undeveloped lands, project siting on developed or agricultural land can also raise significant issues. Moreover, finding land in California without any special-status species is often a tall order.

Regional conservation plans

Accordingly, federal and state regulators are in the process of developing regional conservation plans that will provide streamlined environmental reviews and standardized mitigation obligations for renewable energy projects that impact certain covered species.

Most significantly, a partnership of federal and state agencies is currently preparing the Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) to streamline the regulatory process and establish standardized mitigation obligations for projects in certain areas of the Mojave and Colorado desert regions (covering approximately 22 million acres in seven California counties).

This regional habitat conservation plan is being prepared pursuant to Section 10 of the federal Endangered Species Act and California’s Natural Community Conservation Planning Act and will provide incidental take authorization to the federal, state and local entities with regulatory authority in the plan area. Those entities may then extend their permit coverage to renewable energy and transmission projects under their jurisdiction.

It is anticipated that the DRECP will provide clear, standardized requirements for project siting and mitigation, including in-lieu mitigation fees. These features will provide for expedited permitting and certainty for development timing, financing and construction schedules.

The draft DRECP is expected to be released for formal public review this year. However, it is unlikely that the DRECP will receive final approval until sometime in 2014 - but better late than never.

For solar projects that are located outside the DRECP area or are seeking more immediate project approvals, developers are advised - to the extent possible - to avoid sites containing special-status species or seek coverage under other existing habitat conservation plans, such as the Coachella Valley Multiple Species Habitat Conservation Plan. Conducting biological surveys early in the process may help screen out problematic sites.

Agricultural resources

Given the desire to avoid sites with sensitive biological resources and the need to secure relatively flat land, it is not surprising that many solar developers have targeted California’s rich supply of farmland. However, as most developers will attest, developing agricultural land comes with its own challenges.

In particular, approximately half of California’s farmland is subject to Williamson Act contract restrictions. The Williamson Act, enacted in 1965 to encourage landowners to spare agricultural land from commercial and residential development, enables local governments and landowners to enter into contracts for the purpose of restricting parcels of land to agricultural and compatible uses. In return, landowners receive lower property tax assessments.

Because Williamson Act contracts have automatically renewing terms of at least 10 years, such land generally cannot be developed for solar uses in the near term unless the applicable county or city either determines that solar development of the site is compatible with agricultural use or approves cancellation of the Williamson Act.

Until recently, some local government entities and solar developers chose the first alternative, declaring that solar use was compatible with agricultural use. In doing so, they relied on the general authority of local governments to implement the act and on Government Code section 51238, which provides that electric facilities are a compatible use within an “agricultural preserve.”

The California Department of Conservation, however, recently cautioned that this provision applies only to non-contracted land within an agricultural preserve. According to the department, a proposed solar facility on Williamson Act-contracted land can be deemed compatible only if it satisfies the criteria set forth in Government Code section 51238.1(a). This section requires, among other things, that the use not “significantly displace or impair current or reasonably foreseeable agricultural operations.”

Obviously, it may be very difficult for a utility-scale solar project to pass muster. Thus, Department of Conservation officials have stated, “We do not consider industrial-scale photovoltaic facilities to be compatible uses with Williamson Act-contracted lands.” Developers would be well advised to be cautious in relying on this “compatible use” argument to develop utility-scale solar projects on Williamson Act-contracted land.

This leaves one alternative for developing such land in the near term: cancellation of the applicable contract. While most jurisdictions have been willing to cancel Williamson Act contracts to encourage solar development in their communities (and to conserve water resources that would otherwise be used for agricultural production), there has been increased pushback from agricultural conservation groups that contend that the Williamson Act’s strict cancellation requirements have not been followed.

Most recently, in October 2011, the California Farm Bureau Federation filed a lawsuit challenging Fresno County’s decision to cancel a Williamson Act contract to allow 90 acres of prime farmland to be developed as a large solar project. Although the lawsuit was rejected in December 2012 because the court concluded that substantial evidence supported the county’s cancellation findings, the lawsuit illustrates the increased scrutiny and risks of developing a solar project on Williamson Act-contracted land.

To minimize those risks, a developer should consult with local agricultural groups, site the project on non-prime farmland (if possible) and ensure that abundant evidence supports the required findings to cancel the contract - for example, that there is no proximate non-contracted land that is both available and suitable for the proposed solar development. After all this, to effectuate cancellation, the developer must pay a cancellation fee of 12.5% of the unrestricted fair market value of the property.

To ease the regulatory burden on solar developers, in October 2011, the legislature approved S.B.618 to encourage the development of utility-scale solar PV facilities on marginally productive or physically impaired farmland. S.B.618 provides an alternative method to cancel a Williamson Act contract, whereby the contracting parties may agree to rescind the contract if they simultaneously enter into a “solar-use easement” for a term of no less than 20 years.

Although well intentioned, the procedure has been little used because of restrictions on the eligibility of productive agricultural farmland, the requirement that the Department of Conservation agree to the rescission, and significant costs and uncertainties that remain. The Department of Conservation is currently drafting regulations that may help clarify the process.

Given the difficulty and expense of canceling Williamson Act contracts, developers frequently seek out non-contracted agricultural land. This strategy can reduce some of the risk and uncertainty in developing solar projects, but it is not a cure-all.

Although agricultural sites are usually devoid of special-status species, this is not always the case. For example, Swainson’s Hawks, a state-threatened species, often utilize agricultural fields as foraging habitats. In addition, the governmental permitting authority may require the developer to acquire land or agricultural conservation easements to offset the loss of important agricultural land.

In some counties, finding qualifying land and willing sellers can be challenging and expensive. Nonetheless, although siting a project on agricultural land can be challenging, many developers prefer this alternative to the risks and potential delay associated with siting a project on undeveloped land that may contain special-status species.

Further considerations

An additional consideration for solar project developers is what agency will be principally responsible for approving its project. On the federal side, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM) is principally responsible for permitting most solar projects on federal land in California, and it has taken an increasingly supportive role in approving such projects in recent years.

Most notably, in March, the BLM formally approved two large solar projects in the Southern California desert - the 750 MW McCoy Solar Energy Project and the 150 MW Desert Harvest Solar Project.

Despite these significant project approvals, the BLM has recognized that additional permit streamlining and clarity are required. Accordingly, the BLM has partnered with other federal and state agencies to prepare the DRECP. In addition, in October 2012, the BLM finalized a comprehensive Solar Energy Program to spur utility-scale solar development on BLM-administered lands in six southwestern states, including California.

The Solar Energy Program is intended to provide a clear process and standardized design features (best practices) for solar development in 17 solar energy zones (SEZs). The program also allows for responsible solar development in variance areas outside the SEZs in accordance with an established variance procedure. These clear procedures and a programmatic environmental impact statement from which the BLM can tier project-level environmental review should accelerate the permitting process on federal lands.

On the state side, cities and counties are generally responsible for permitting PV solar projects, whereas the California Energy Commission is responsible for permitting solar thermal projects with a generating capacity of 50 MW or more. The speed and clarity of the permit process can vary significantly depending on the applicable permitting agency. Although some government authorities have developed a reputation for fast and flexible permitting, others are considered slow and uncompromising. An experienced practitioner can help a developer identify the “friendly” jurisdictions and guide a project through even the most cumbersome process.

A broader concern for developers in California is the time, expense and uncertainty associated with environmental review pursuant to the California Environmental Quality Act (CEQA). For large utility-scale solar projects, the environmental review process can take two years or more and result in uncertain project approvals that could likely be subject to judicial challenge by disgruntled project opponents.

Although the process and substantive standards for CEQA review are not likely to change in the near future, the legislature has taken an increased interest in limiting and streamlining CEQA lawsuits. Specifically, in 2011, the legislature approved Assembly Bill 900, which provides judicial streamlining for certain “leadership projects” that the governor certifies. To date, this fast-track procedure has been used sparingly, and only one solar project - the McCoy Solar Energy Project - has been certified by the governor.

More significantly, this year the legislature is considering comprehensive CEQA reforms. State Senate President Darrell Steinberg is leading the charge and has introduced S.B.731 as the starting point for discussions.

Although it is unclear what CEQA reforms will result, solar developers should keep a close eye on S.B.731 and several other bills that are working their way through the legislature this year. Many of the bills are aimed at easing the regulatory and permitting burdens associated with developing solar projects in California. S

Industry At Large: State & Local Policy

Numerous Considerations Affect Speed And Ease Of California Development

By Andrew Oelz & Adam Umanoff

Picking the right site is only the first - and perhaps most simple - part of the equation.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph