301 Moved Permanently

On Sept. 23, four California and federal resource agencies released a 22.5 million-acre draft endangered species conservation plan for Southern California. The plan - which has been nearly six years in the making and will cover 37 species across almost a quarter of the state - seeks to streamline the endangered species permitting process for utility-scale wind, solar, geothermal and transmission facilities while conserving desert species and their habitat on a landscape scale.

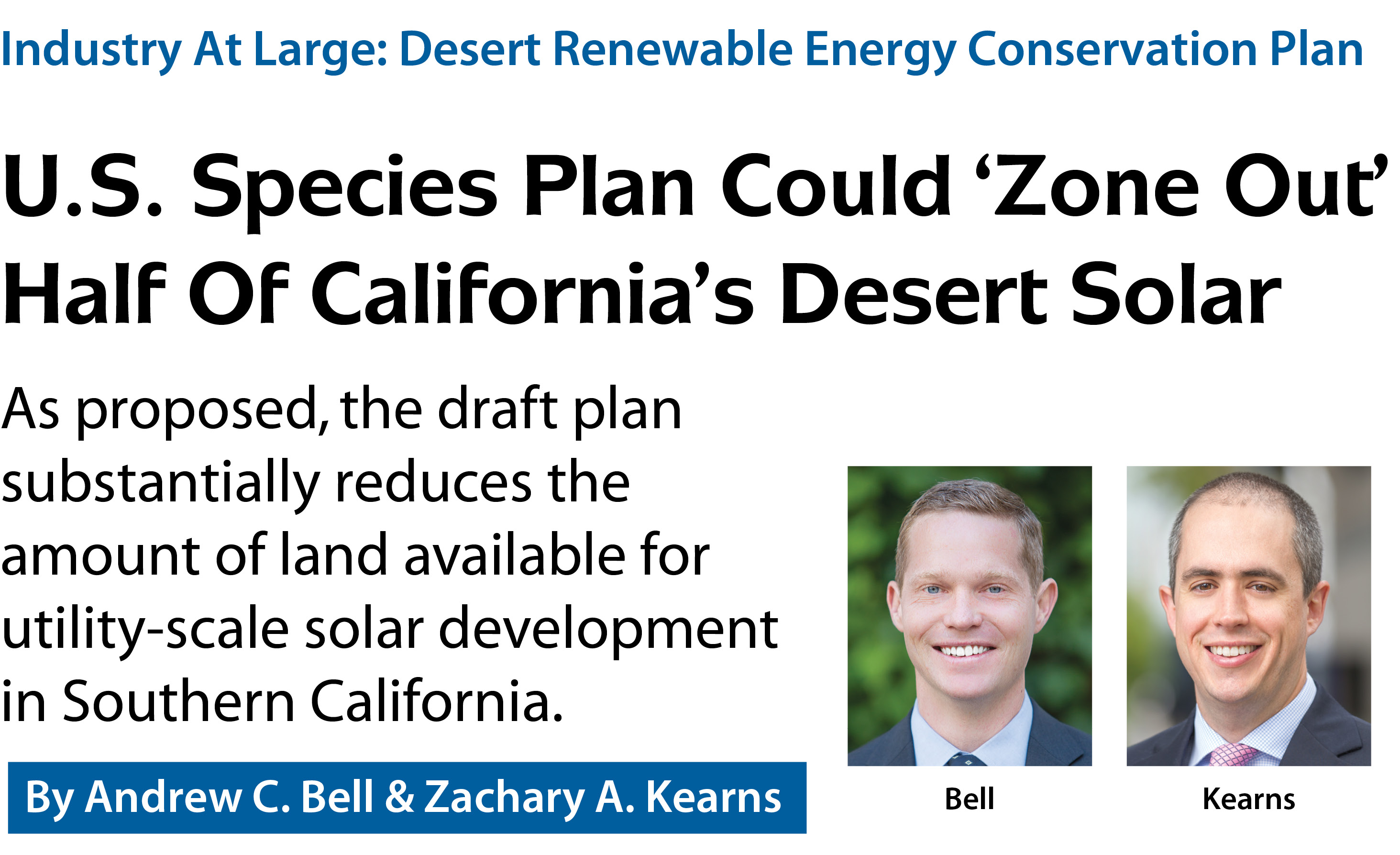

However, in doing so, the draft Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan (DRECP) also designates where renewable energy projects can and cannot go, both directly through U.S. Bureau of Land Management (BLM) land use plan amendments that prohibit renewable energy development, and indirectly through stringent avoidance and mitigation standards within the Development Focus Areas (DFAs) where renewable energy development would be allowed.

In sum, the preferred DRECP alternative would remove approximately 6.2 million acres from potential development and target another 1.1 million acres of non-federal lands for future conservation. 7.6 million acres of the 22.5 million-acre plan area are already off limits to renewable development and another 5.5 million acres are already subject to military, urban, tribal and recreational uses. By contrast, the DRECP would designate just over 2 million acres - less than 10% of its total area - as DFAs.

The draft DRECP will substantially affect the solar sector in California. Of the 2 million acres identified for solar development by the Center for Energy Efficiency and Renewable Technologies, less than half (965,104 acres) would be available under the preferred DRECP alternative, with the remainder rejected on the basis of potential resource conflicts with DRECP goals and agency objectives.

Other recent landscape-scale solar planning efforts would be scaled back as well: 575,000 acres of “variance lands” currently open to solar development under BLM’s 2012 Solar Energy Program would be off limits under the preferred DRECP alternative, leaving a remainder of only 13,000 acres of variance lands for development, but without the streamlined species permitting benefits of the DRECP.

Finally, because California’s deserts are largely un-surveyed, the new lines drawn by the draft DRECP have, for the most part, been proposed on the basis of landscape-scale models, with little ground-truthing and without a clear mechanism for verification and potential correction at the project level.

The public comment period on the DRECP’s joint draft environmental impact statement and environmental impact report ends on Jan. 9, 2015. Comments from renewable energy companies and the environmental community will no doubt be voluminous as they strive to realize their oftentimes competing visions for California’s utility-scale renewable energy industry. The dialogue will be loudest over the location and size of conservation areas that mostly prohibit development and DFAs that do not. The feasibility of standardized avoidance and mitigation measures prescribed by the DRECP will also be debated.

It will be important for the industry to interact closely with state and federal agencies tasked with the DRECP, both as a local matter for California’s solar sector and nationally as a precedent for other large-scale species conservation efforts that could affect solar development outside the state.

Streamlined species permitting or desert rezoning?

The stated principal goal of the DRECP is to front-load and streamline the California and federal endangered species permitting processes for utility-scale wind, solar, geothermal and transmission projects in California’s deserts, while at the same time, mitigating the projects’ effects through the creation of a reserve system on a comprehensive, ecological scale.

At its core, however, the DRECP would function more like a land use plan by designating certain areas as compatible with renewable energy development and setting others aside for conservation. This “zoning effect” is largely a consequence of the DRECP’s proposed reserve design, which relies heavily upon prohibiting renewable energy development on over 6 million acres of public lands administered by the BLM, including the 575,000 acres of variance lands referenced above. This is in contrast to the proposed DFAs, 80% of which would occur on private lands.

DRECP compliance on private lands would be voluntary in theory, but potentially less so in practice. As it stands now, the draft DRECP provides resource agencies, local governments and the conservation community with a readily available framework for the quick assessment and mitigation of almost any utility-scale renewable project proposed within the DRECP area, regardless of whether the DRECP is ever approved. Renewable projects proposed on private lands are therefore likely to be “soft-zoned” by the DRECP even if they or their local jurisdiction opt out of the program.

In addition, the California law that supports the DRECP contains express provisions for the review of all projects within the DRECP area for consistency with its goals and objectives. This requirement applies even before the DRECP is adopted and regardless of whether a project seeks incidental take authorization under the DRECP. And while the draft DRECP does include grandfathering provisions for some projects, the substantial evidence it creates can still be applied in comments on a project’s environmental impact review.

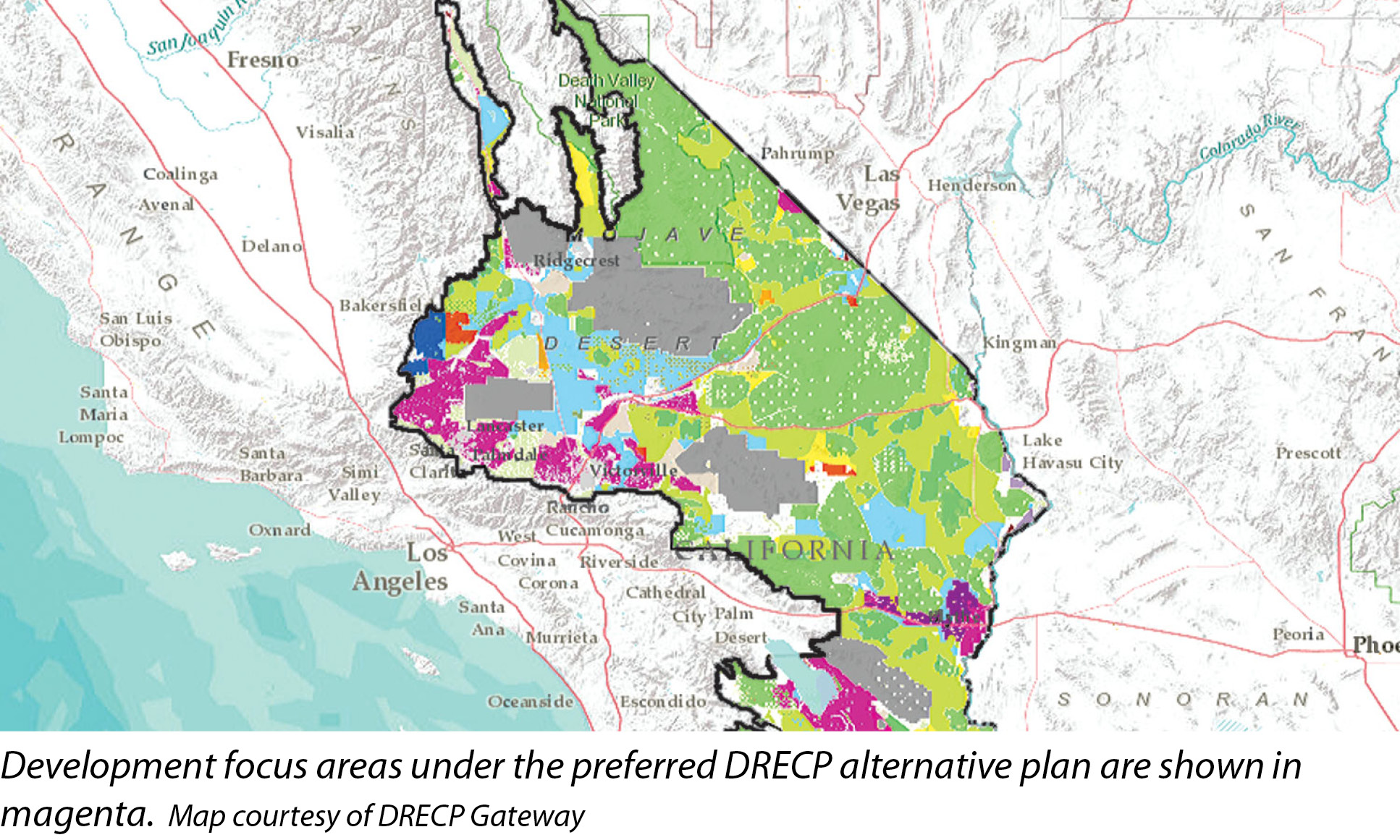

As stated above, the zoning effect of the DRECP would have a particularly pronounced influence upon solar development, even though the California deserts contain some of the best undeveloped solar resources in the world.

Even within DFAs, renewable energy projects must prepare and submit formal applications to obtain streamlined species permitting under the DRECP. The draft DRECP contemplates a 14-step process that includes preparation and submittal of an integrated project proposal comprising a thoroughgoing assessment of all applicable site survey, avoidance, setback and operational standards of the DRECP.

This, in turn, would be followed by a DRECP consistency review that, if successful, would lead to acceptance of the project’s application and review of project-level technical studies and impact reviews. Streamlined species permitting decisions would be expected within one year of submittal of a complete application, or longer, if required for technical studies.

Projects that are inconsistent with the DRECP or outside a DFA presumably would be subject to a lengthier and more restrictive review process by the California Department of Fish and Wildlife and the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service.

Avoidance and mitigation standards

Projects proposed within DFAs would still need to comply with substantial avoidance and mitigation standards that may be extremely difficult to satisfy in practice.

For example, DFA projects would be required to set back up to 0.25 miles from riparian resources to the maximum extent practicable, with exceptions being limited to “unavoidable impacts” defined as “minor intrusions to biological resources, such as a necessary road or pipeline extension across a sensitive resource required to serve a project.” This could be almost impossible for even smaller-scale projects to achieve, given that state-jurisdictional ephemeral streams pervade the California deserts like capillaries under skin.

Other examples include a prohibition of DFA development within one mile of a golden eagle nest and a restriction against development within DRECP-designated desert tortoise linkages if deemed to compromise the function of the linkage.

Under the preferred DRECP alternative, unavoidable impacts within a DFA would require compensatory mitigation at a default ratio of 1:1 and a higher 2:1 ratio for DFA development within certain desert tortoise linkages and Mohave ground squirrel population centers. Another DRECP alternative would increase these ratios to as high as 5:1.

The impact of utility-scale solar on avian species has been an intense focal point this year. While the draft DRECP generally defers to the Bald and Golden Eagle Protection Act permitting program for potential golden eagle impacts, it contemplates a separate and relatively novel compensatory framework for other avian species based on a resource equivalency analysis.

Under this approach, compensatory mitigation would take the form of habitat preservation at a level deemed to provide a population productivity gain roughly equivalent to the number of life years lost by any take caused by a project. The take of a single Yuma clapper rail, for example, would require 2 acres; the take of a Gila woodpecker would require 24 acres. Under this approach, mitigation would not be required unless a take actually occurred.

Rebuttable presumption

The DRECP’s use of multiple landscape-scale models to infer and prioritize ecological values across 22.5 million acres is extraordinary. But large-scale models require large-scale assumptions that cannot always depict conditions on the ground accurately.

For example, earlier iterations of the DRECP incorporated a desert tortoise habitat model that did not account for anthropogenic disturbance, thereby overvaluing previously disturbed project sites. While that particular instance may have been remedied in the latest draft through the overlay of a habitat intactness model, project-level discrepancies will no doubt continue to occur.

The draft DRECP does include an adaptive management component, but that mechanism focuses on the effectiveness of the overall reserve design and is founded on the premise that the DRECP’s resource modeling assumptions are correct. There appears to be no provision for the use of site-specific survey data to rebut or correct the DRECP’s broad use restrictions. This is particularly problematic when the current draft could deprive Southern California of a significant portion of its remaining utility-scale solar potential.

As proposed, the draft DRECP substantially reduces the amount of land available for utility-scale solar development in Southern California while tightening limitations over the remainder. Any adjustments will require vigorous industry engagement backed by specific, substantive comment prior to Jan. 9 of next year. S

Industry At Large: Desert Renewable Energy Conservation Plan

U.S. Species Plan Could ‘Zone Out’ Half Of California’s Desert Solar

By Andrew C. Bell & Zachary A. Kearns

As proposed, the draft plan substantially reduces the amount of land available for utility-scale solar development in Southern California.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph