301 Moved Permanently

Massachusetts’ solar policies, including solar renewable energy credits (SRECs) and net metering, are an unquestioned success in creating green jobs and clean energy while protecting taxpayers. As the SREC program enters its second phase and net-metering caps are reached, it’s time for Gov. Charles Baker to reaffirm the state’s commitment to a sustainable economic future.

Former Gov. Deval Patrick established the SREC program in 2008 to spur 400 MW of new solar power in the commonwealth. Under the program, solar arrays earn one “credit” for each megawatt-hour of energy generated, with credits auctioned off in competitive bidding to provide support as the industry matured.

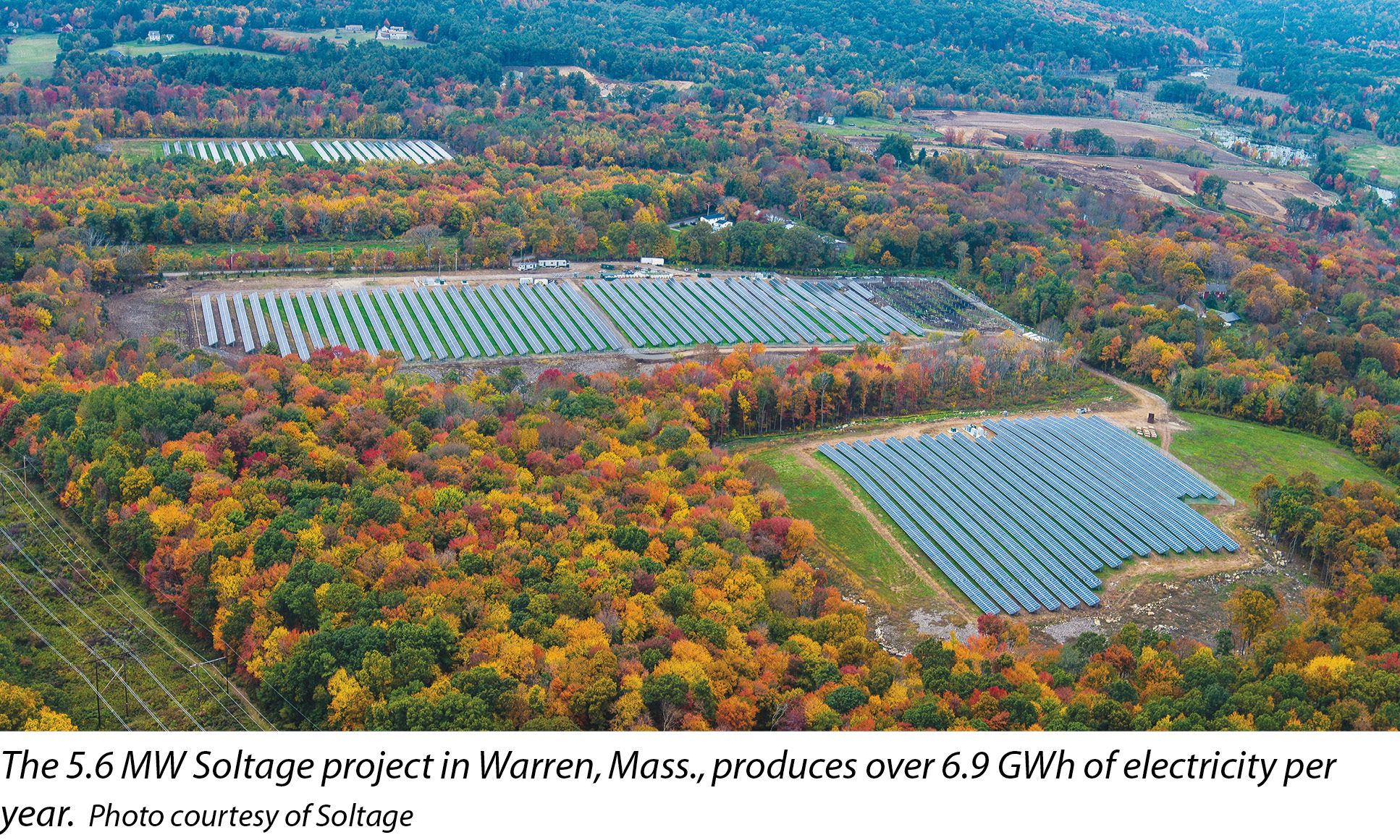

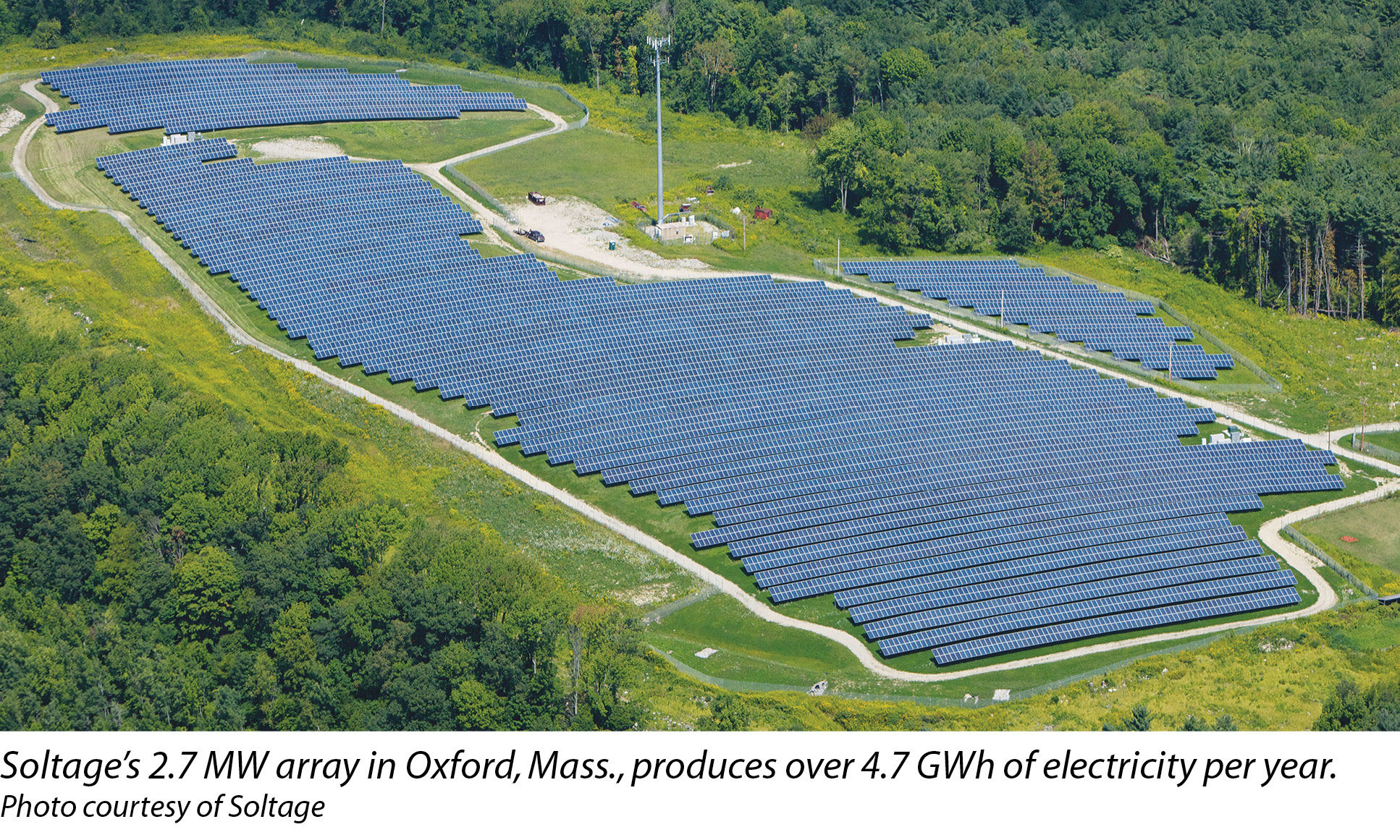

It worked. The program met its target three years early as gleaming rows of solar panels sprouted up on fields, commercial and government property, and even landfills. Massachusetts now has 752 MW total installed solar capacity, according to the Massachusetts Department of Energy Resources (DOER). Further, the Massachusetts Clean Energy Center reports there are 12,122 solar workers employed across 1,415 businesses throughout the state.

Clear direction, responsible incentives

SRECs enabled this surge by sending clear signals about what types of installations the state wanted. This has ensured stable incentive pricing for solar developers and has empowered utilities to facilitate zero-emission electricity. But instead of extending the program once its goals were met, Massachusetts went further by increasing the target to 1,600 MW by 2020 with eligibility limits on new development.

Under the second SREC phase, new projects are directed toward homes, small businesses, landfills and community projects while minimizing state and ratepayer costs. SREC II, as the new phase is called, reduces the value of solar credits every year through 2030 as installations rise and project costs fall.

Cutting incentives over time is an incredibly strong market feature. By providing stable incentive pricing and long-term guidance on market targets, solar developers and owners can bank on their project’s value while preventing overcapacity.

SREC II also creates the incentives that solar development regulators want across the state. Arrays for homes, carports, communities and emergency power receive full credit value, while commercial building projects receive 90% of a credit and those on landfills or brownfields receive 80%. Larger projects on commercial and agricultural properties - most of the initial 400 MW - receive 70% of a credit, with truncated capacity targets relative to the rest of the market.

Directing development toward underserved markets helps SREC II build stronger communities. Environmentally contaminated sites become productive once again, homeowners and businesses lower energy costs, and those who can’t install solar on their property can join community-based projects.

Contrast SREC II to other SREC markets and its value becomes clear. In New Jersey, projects were built too fast. In Pennsylvania, regulatory tweaks allowed out-of-state projects to count for in-state targets. SREC prices spiked then collapsed virtually overnight in both states. Massachusetts addressed these risks in the SREC II program design rollout, and investors have gotten comfortable with the market construct.

SREC II incentives are also expected to be priced 30%-50% below SREC I levels without undercutting new investment. Rational state programs must recognize that solar costs are falling and benefits given three years ago are not necessary today. Indeed, average solar project costs have fallen 45% nationwide since 2012, and I expect that trend to continue with at least a 10% decline in average costs through this year.

Doing more with less

In the future, solar markets will need fewer benefits to achieve the same level of growth. SREC I prices moved from $570 in 2010 to $270 in 2013, while the SREC II price floor auction mechanism started at $300 in 2014 and will decline to $199 in 2024. This reduction provides price support while preventing overcompensation by matching expected project and capital cost decline.

In fact, SREC II will likely generate additional private investment. DOER estimates Massachusetts residential solar alone will require $600 million in loans, and local banks are heeding the call. Regional banks are rarely the first movers into a new asset class, but those in Massachusetts and the Northeast have watched solar’s rapid growth and created tailored loan products for residential, commercial and small utility projects.

My company’s most recent Massachusetts project, a 1.8 MW system under construction in Brookfield, demonstrates new investment through SREC II. The project is part of a fund jointly financed by U.S. Bancorp, North Sky Capital’s CleanTech Alliance Fund and GoldenSet Capital. The array will go online this year, supplying clean energy with reduced utility bills to Quinsigamond Community College for years to come.

SREC II is an important solar industry driver, but state policymakers should also consider legislation introduced to extend Massachusetts’ net-metering cap. Currently, only about 27 MW remain under the public cap, and although more space remains under the private caps, those are also quickly shrinking.

Once these caps are reached, new solar assets expecting to sell power to the grid through net metering won’t be able to do so if they are selling to an entity like a municipality or public entity in the state of Massachusetts. This will create headwinds for new development - anytime developers face uncertainty in their ability to interconnect assets and capture anticipated revenue, new projects and new investments will slow down until the obstacles are addressed.

Don’t step backward

With such a positive track record of solar investment and growth, it’s hard to think the SREC II system should change. However, a 2014 state legislature bill would have done just that by separating future SREC incentive systems and establishing a “minimum bill” for solar system owners who generate more power than they use. SREC II continues to prove a healthy SREC market drives development - let’s not kill something that creates a net gain.

In addition, allowing the public and private net-metering caps to be filled without an expansion creates growing pains in a rapidly expanding market that could and should be avoided. In the short term, policymakers should raise net-metering caps by rapidly pushing through regulation to increase the caps on both the public and private sides of the market.

In the long term, any new program should be fully vetted before being signed into law to ensure it attracts the same level of investment as existing programs - with an eye to not overhauling any regulatory programs that are already working well, unless we are convinced that the successor program is a much better option.

Gov. Baker and Massachusetts have already faced a significant state budget shortfall. As his administration works to close future gaps while encouraging growth, we encourage him to preserve SREC II and expand net-metering caps - two fiscally responsible programs that drive economic success while protecting our environment.

Industry At Large: Massachusetts Solar Incentives

Massachusetts’ SREC II Program Is Worth Preserving And Expanding

By Jesse Grossman

There are good reasons for keeping the highly successful incentive program going strong.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph