301 Moved Permanently

Reducing soft costs has become the holy grail of solar. However, the wrong soft costs - marketing and customer acquisition - are being targeted.

An entire industry of solar support businesses - from lead providers to software companies claiming to have the ultimate roof qualification tool - has emerged to reduce installers’ customer-acquisition costs. That was to be expected. In addition, state programs like Solarize Massachusetts aim to reduce installers’ soft costs and make solar more economical for consumers by shifting the marketing responsibility to communities.

That focus is misplaced. Don’t get me wrong: Having Solarize communities actively engaged in marketing is a huge factor in the success of those programs. Yet, every industry has customer-acquisition costs and you don’t see state agencies running out to help, for example, the intrusion and fire alarm industry to acquire more customers at less cost.

The real enemy is administrative soft costs - especially those in New England, where we regularly interface with state agencies, almost 30 utilities and hundreds of local municipalities. Administrative soft costs related to rebates, interconnections, permitting and inspections nibble at installers like ducks of many species. Each takes a bite of time and budget, and many get fatter as the fledgling industry grows.

Rebate ducks

At the beginning of Massachusetts’ successful and recently concluded solar rebate program, rebates were substantial, reducing system prices by 30% to 50%. As planned, rebates declined over time along with the cost of solar. Unfortunately, the installer overhead associated with processing rebates did not change. It took as much effort to secure a customer rebate of $1,250 in 2014 as it did for a $20,000 rebate in 2008.

Toward the end of the Commonwealth Solar Rebate program, we seriously considered forgoing the application, monitoring and processing of the rebate and simply discounting our prices by the rebate amount instead. It probably would have been more cost-effective for us. But, that trade-off would have been hard to convey to buyers and would have given an edge to competitors touting the rebate. So, there was no way to keep that duck at bay.

Utility ducks

Three big investor-owned utilities (IOUs) serve much of Massachusetts, but the state also has 41 municipal light plants (MLPs). Established via individual pieces of state legislation, MLPs do not fall under the same regulatory jurisdiction as the IOUs. They answer to local officials and, essentially, change the solar rules as and when they please.

Net metering, in particular, has become a quagmire of inconsistent policy among MLPs. Some provide full retail net metering, some offer wholesale net metering at a rate typically about half of retail, and some don’t net meter at all.

Some MLPs are reneging on net metering - changing from retail to wholesale or, in a draconian move, eliminating net metering altogether. This move prompted a huge backlash from solar owners in one particular community we serve. In the end, the MLP grandfathered existing systems at a lesser rate - 36% of retail - and killed net metering for future systems.

It often feels like the MLPs are part of the war on solar being waged and funded by utility-backed groups and national interests intent on killing it off. Radical shifts in policies do untold harm to the industry by injecting uncertainty into the economics, and they keep installers scrambling to adjust their numbers.

Just staying on top of the changes and their impacts represents an administrative burden that any business owner could appreciate. Invest company time in actually attempting to sway public policy - over and above time used to just monitor and adapt to it - and you invite an even bigger duck to nibble at your leg.

But, what choice does an installer have? My salespeople understand net-metering policy at a level rivaled only by state regulatory attorneys. They have to. If we misstate an MLP policy in a proposal, the customer’s economics - including payback - will be wrong.

Requirements and processes for rebates and interconnections also vary by MLP and change regularly. Even IOUs - which usually have consistent, if cumbersome, processes - can throw a wrench into the works. IOU Unitil has halted new solar interconnections on a specific branch circuit until it can undertake a study - rumored to cost $250,000 - on how to protect the grid during peak solar production. Rumor also has it that Unitil wants the solar industry to pay for the study!

Inspector ducks

The complexity of dealing with nearly 30 utilities pales in comparison to working with hundreds of cities and towns on building and electrical permits and inspections - a problem for installers nationwide. The joke in Massachusetts goes like this: “There are 351 different cities and towns here, and 351 different sets of (fill in the blank with your choice of zoning regulations, building inspectors, electrical inspectors, permitting processes, permitting fees, etc.).”

Budgeting for local permitting and inspections is a challenge. Building permit fees range from $50 to $1,000, and wiring fees range from $50 to $750 - at least, as of press time. A recent 14 kW solar photovoltaic installation required a $587 electrical permit, whereas the electrical permit for an entire new house in the same town only costs $250. Fees of $1,000 or more substantially change the economics of a system - extending the consumer’s payback time - unless the installer chooses to eat that cost, which would take a bite out of profits. Either way, someone is nibbled by another duck.

Nor are the fees set according to a common formula. Some municipalities base electrical inspection and permit fees on the number of kilowatts, some on the number of panels and some on a percentage of the project cost. A fee of 1% of the system cost has been typical, but in a disturbing trend, fees are now increasing by 100% to 200%. One town inspector admitted he established his fee structure to extract revenue from the big solar farm developers. Higher fees benefit more than just the communities; some inspectors are paid commissions on their fees. Too bad no one is considering the impact of these fees on town residents and the smaller, local installers trying to make a living.

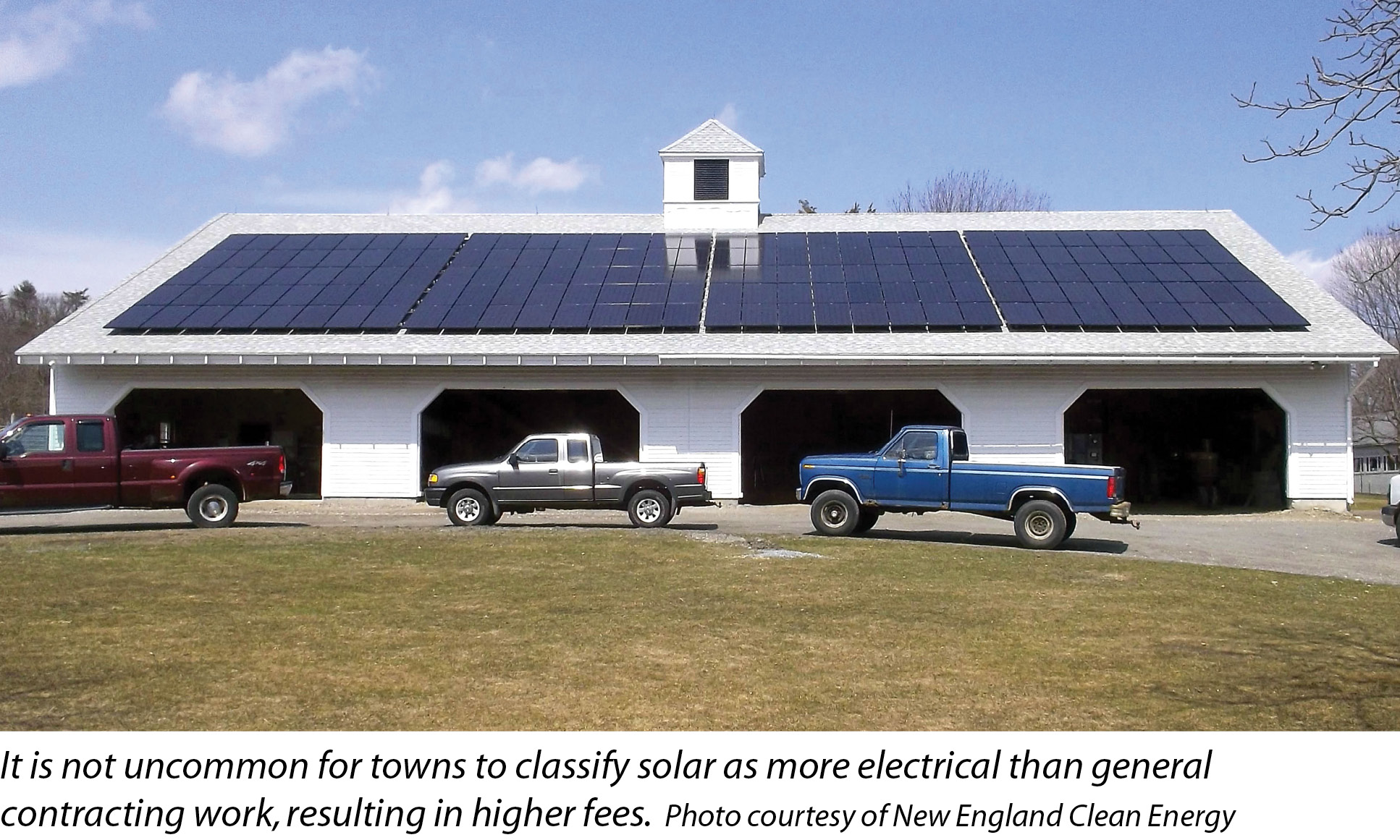

In another disturbing development, one town now defines more of the solar job as electrical work instead of general construction work, which would fall under the building permit. This creates higher permitting fees for installers and more revenue for the town and inspector, given that electrical fees are based on a higher percentage. No need to have the local police target out-of-town speeders when revenue needs a boost!

Yet another trend is that municipalities require more work from installers. For example, some municipalities now ask for an external disconnect beyond utility and code requirements, citing safety. With no disrespect to local inspectors, such a move demonstrates a lack of knowledge about the technical workings of solar.

Inspectors justify fee increases as compensation for their learning curve on solar, which eats up their time. But the changes to rules and fees often feel arbitrary. Upon learning who we were, i.e., a local company doing quality work, one town waived the rule that requires us to drive an hour to hand-deliver an application. This is better than the alternative, but the overall uncertainty is frustrating when trying to run a business.

Competitor ducks

Some of the challenges facing installers are being created from within. Local inspectors are increasingly anti-solar because of the second-rate work they see from the installers they call “the transplants” - the out-of-state companies, mainly national leasing companies, that do sub-par work, submit incomplete documentation and don’t follow through on their pieces of the process. Conscientious installers are paying the price for sub-par work by other installers.

Although the motivations for towns wringing more money and work from solar installers vary from revenue generation to safety concerns to distrust of installers, the end result is the same: nibbled to death by ducks.

Each nibble of our time and budget by a utility or municipality starts out as a mere annoyance, but put them together and they add up to a considerable bite out of time and profits. And they make solar less affordable for consumers.

In a perfect world, state agencies would tackle the inconsistencies between utilities and between towns and help to reduce those damaging administrative soft costs that “nickel-and-dime” installers. At the end of the day, I expect to have marketing costs, and I can control them. But installers and, therefore, their customers are at the mercy of unexpected policy-and-fee-change ducks nibbling away at their businesses and the industry.

Industry At Large: Installer Soft Costs

It’s Getting Harder For Installers To Duck Solar Soft Costs

By Mark Durrenberger

Despite publicized efforts, a growing flock of costs is nibbling away at profits and the health of the industry.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph