301 Moved Permanently

The Latin American solar market is shorthand for a tremendous variety of geographic, environmental, cultural, political and economic conditions that render the term almost meaningless. Almost.

In its broadest concept, the region could host arrays in jungles, deserts low and high, urban rooftops and even islands, if you tack on the Caribbean, as some companies do. Today, solar firms that are setting up offices and appointing business and project managers with responsibility for such a tremendous swath of the globe will no doubt broaden their organization tables as regional priorities come to the fore.

But, you have to start somewhere, and Latin America - if you’ll pardon the shorthand - is one of the world’s most attractive developing markets for solar power. Companies with experience in the region are the first to point out that successful project development requires immense patience and firm relationships with local partners. Moreover, not every country is created equal. Nevertheless, the rewards can be great because some of the world’s best irradiance resources and economic arguments for going solar can be found there.

Lands of opportunity

“In our experience, Latin American markets work, in general, much better than the northeast U.S., Japan, U.K., Germany and many other countries that currently have higher levels of solar penetration,” says Camilo Patrignani, CEO of Greenwood Energy. “Areas like northern Chile, northern Mexico and southwest Peru are the most promising markets.”

Companies looking to successfully invest in solar projects in the region have to do a lot of homework. First is determining which regions are most promising in terms of production. Nico Johnson, senior project developer for Latin America and the Caribbean at Conergy, says the vast differences in topography and climate from one side of one country to another - let alone the entire region - make modeling for solar interesting, to say the least.

“Pretty much anywhere you find arid, near-coastal climates and good trade winds as compared with tropical lowlands, you’re going to see improvements in solar production yield, which is a key lever in a solar project having good economics,” Johnson says.

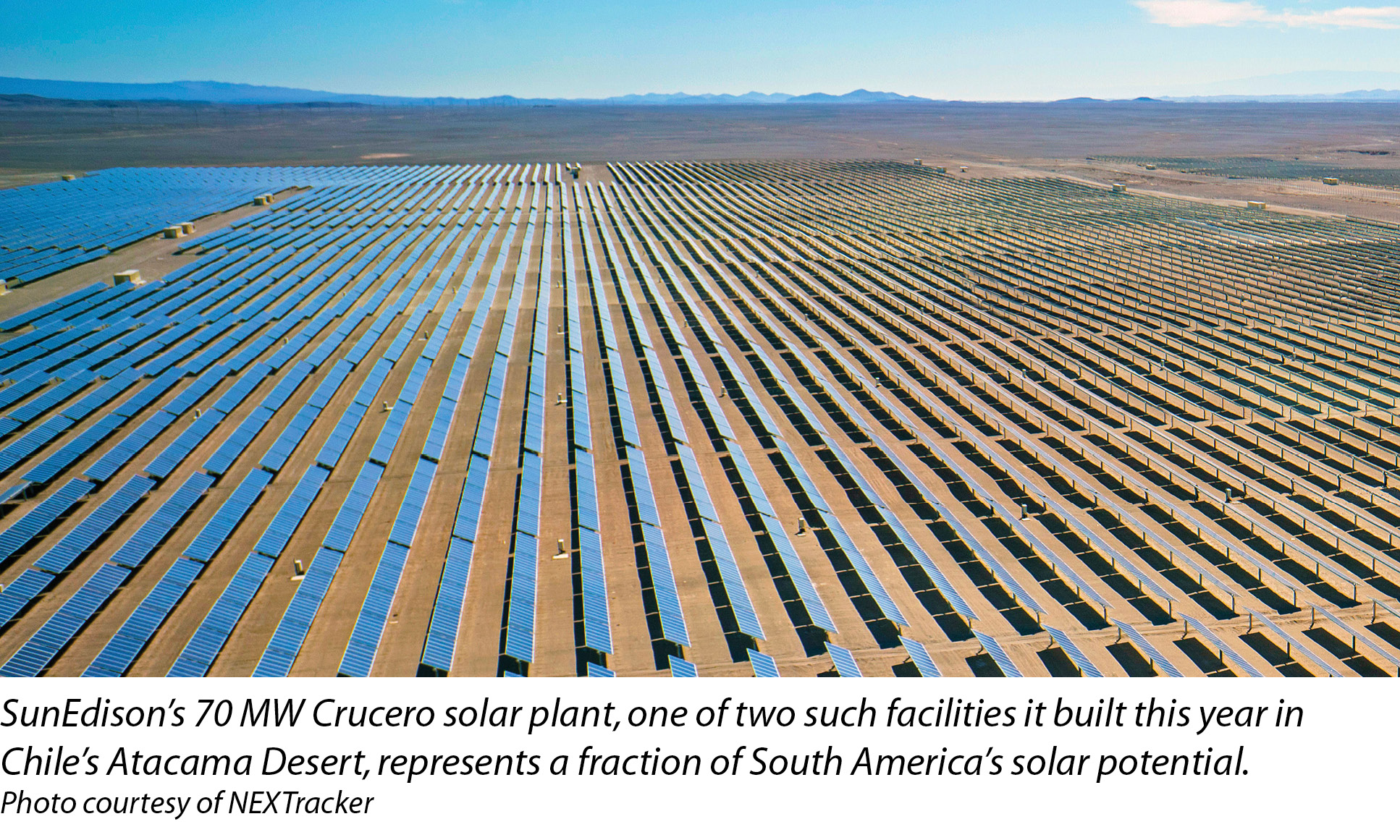

In Panama, for example, the irradiance near the Azuero Peninsula, where the country is more arid and winds keep the clouds dispersed more consistently, you can see a 27% increase in kilowatt-hour per kilowatt-peak (kWh/kWp) yield compared with sites closer to the capital in the northwest of the country. Similarly, irradiance in the arid Atacama Desert in Chile is among the highest in the world - which is one of the key reasons why Chile has been a hot solar market the last few years.

“When you are able to get over 2,000 kWh/kWp consistently, it makes the project economics work much better than in areas where the norm is closer to 1,600 kWh/kWp or lower,” he says, adding that irradiance is particularly important in Latin America, where, generally speaking, projects do not receive the benefits of government-sponsored incentive programs, such as renewable energy credits or significant tax credits.

Johnson points out that Latin America has become the fastest-growing market in the world in large part because of its ability to scale without these types of incentives. The reason for this has been the price of fossil-fueled generation. Chile was one of the first markets to reach grid parity on solar pricing. Panama is there now, and Mexico will be soon. Certain other markets, such as Peru and Ecuador, could be very soon.

“I think this is one of the factors that has limited the growth potential of Central America compared with Mexico and Chile, despite the fact that the actual market economics of wholesale and retail pricing are better suited for solar than just about any other Latin America market,” Johnson says.

At the same time, the same economics could provide an opening for distributed generation (DG) projects, which tend to pencil based on electric rates. Johnson says he expects a surge in DG projects in Central America for this very reason.

Greenwood Energy’s Patrignani reports that Panama is the first nation in that region where DG projects are already taking off. Perhaps not surprisingly, it is also one of the few Latin American countries that have established solar incentive policies.

“Given that Greenwood’s current focus is in distributed generation, net metering in Panama has been particularly helpful to us,” Patrignani says. “Panama’s net-metering program covers projects up to 500 kW capacity - and several parties are pushing to extend the program to projects up to 1 MW, which will be great.”

Johnson adds that Honduras includes capacity payments as part of the calculation of energy price in power purchase agreements (PPAs) with the Empresa Nacional de Energía Eléctrica, the government-owned utility. Although there are many ways that capacity can be calculated, it is generally agreed that, for the most part, solar generation contributes to the overall capacity requirement - or reduction - in peak demand that a distributor or utility would be purchasing as a component of a solar PPA. “This is the sort of policy we would like to see proliferate,” he says. “This economic benefit would be of great leverage in places like Panama and Colombia, where the capacity payment would help mitigate the currency risk and possibly even the spot market risk.”

In addition, there are existing energy supply arrangements in some markets that arose prior to the emergence of solar as an alternative - and as competition - to status quo suppliers, such as government-owned energy suppliers. Many of these arrangements were for the benefit of commercial interests that otherwise would have had to buy a lot of energy at high rates, which tend to cover costs for subsidized lower-tier residential users.

Johnson says the energy market in Mexico provides a great example of such “self-supply” arrangements that existed prior to the current energy reform. “These arrangements created a virtual net-metering capability with very low transmission toll charges that looks very similar to the state of Connecticut’s virtual net metering, for example,” he says. “Folks with these old self-supply projects, which are grandfathered, are sitting on very valuable potential solar projects.”

Throughout the region, many governments are staging capacity auctions to attract solar project development. Earlier this year, Brazil awarded a total of 833 MW in its competitive auction - of which Conergy secured 60 MW for two utility-scale projects in the northeastern municipality of Paraiba.

Points of access

Greenwood Energy, working as a developer or providing engineering, procurement and construction services in partnership with other developers, cherry picks the projects in which it involves itself. Not only are certain regions more productive in terms of irradiance, but some are more attractive than others when it comes to doing business. Without casting aspersions, they key to success in developing in any market is to establish relationships with local champions. This goes for getting the green light in a New England town just as it does for getting a permit in Central America.

According to Patrignani, the important difference is that solar is a new industry in Latin America, so it is very difficult, if not impossible, to find local partners with development experience. At the same time, prospective developers absolutely need to hire local teams to interface with clients and governments. “The long and short of developing local expertise is that the process just takes time,” he says.

Greenwood Energy’s experience with developing utility-scale projects in Latin America has moved the needle toward DG projects - at least for those it is bankrolling. The main reason for this, Patrignani says, is that things don’t always move at an acceptable pace when it comes to governments and public agencies. Depending on the market, this could be due to permitting - as in Chile - or the effects of ongoing regulatory reform - as in Mexico. However, once all of the papers are signed, utility-scale projects tend to move along at a good clip. Chile, for example, allows the importation of personnel and material from Europe or the U.S. essentially without restriction.

The trick is getting to that point. If the goal is to get deals done quickly, many other options exist to develop solar projects, especially with commercial clients. Intriguingly, Patrignani says DG projects, which are less complicated logistically, tend to have more restrictions in terms of local labor and material requirements. “Forming local teams is critical to supplying the market in a programmatic way,” he says.

Johnson adds that achieving capital commitment for projects in Latin America is typically a longer process than people expect. He says developers should count on five to six months for capital commitment and disbursement - and that’s the best-case scenario if a multilateral entity, such as the Overseas Private Investment Corp. or the Inter-American Development Bank, is involved in the deal.

The issue of security is one that should be mentioned. High-profile projects in remote locations, such as Chile’s Atacama Desert, are easy to secure with government cooperation and difficult for bad guys to reach. Elsewhere, DG projects behind chain link fences in the countryside or even in some cities can be more problematic. Conergy’s Johnson says his company’s approach is to manage construction with local personnel and not have crews move from country to country. “This mitigates personnel risk and leverages each country’s existing expertise and cost of labor,” he says.

Business as usual

Latin America is not likely to present too many challenges in terms of specialized equipment requirements. With a few exceptions, certification requirements tend to default to either Underwriter Laboratories or International Electrotechnical Commission specifications.

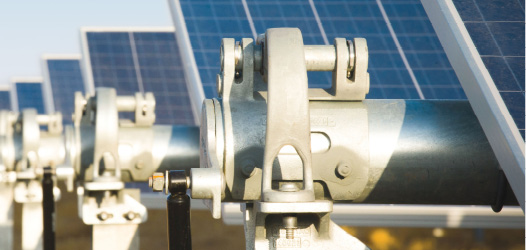

Dan Shugar, CEO of NEXTracker, says that his company’s Self-Powered Tracker (SPT) systems do not require any special certification for operation in the various markets in the region. In September, the company completed its shipments of SPT single-axis trackers for the 110 MW Quilapilún power plant SunEdison is developing in Chile’s Santiago metropolitan region. Last year, the company supplied two other large-scale projects with SunEdison in Chile - both in the Atacama Desert. Shugar says using the same teams on the ground for each project in succession has improved the process.

“When the materials arrived in the desert for the first SunEdison project, Crucero, we were there,” Shugar says. “We were driving those first piers into the ground with SunEdison and its contractors. Together, we derived methodologies to deploy the systems faster. The actual construction time of the first 70 MW system was 12 weeks. Construction of the second 70 MW project was eight weeks.”

Solar In Latin America

Latin America Beckons As Solar’s New World

By Michael Puttré

Developers must pick their strategies carefully in a region of diverse climates and policies.

si body si body i si body bi si body b

si depbio

- si bullets

si sh

si subhead

pullquote

si first graph

si sh no rule

si last graph